(un)affordable - the art of appreciation

28. March 2024

#1to1dialogues

Welcome to our fifth edition of 1:1 DIALOGUES. Our guest is Gerald Mertens - since 2001 managing director of unisono, the German Music and Orchestra Association, working as a lawyer in Berlin, and also chairman of the Netzwerk Junge Ohren. He hosts the wonderful podcast „Klangvoll - aus dem Maschinenraum des Musikbetriebs” for Schott Music, where Franziska spoke about 1:1 CONCERTS last month. Here comes the return invitation.

(Un)affordable?! A somewhat provocative title that points in several directions. Our diverse German theatre and orchestral landscape is a priceless treasure; in 2014, the German UNESCO Commission added the theatre and orchestral landscape to the national list of intangible cultural heritage. At the same time, however, freelance artists have barely been able to secure their livelihoods with their art, especially during the pandemic. The question arises again and again: how much should culture cost? Today, Franziska talks to Gerald Mertens about the affordable and the unaffordable, about value and appreciation.

Franziska im Gespräch mit Gerald Mertens. Insta Live jetzt auf Youtube nachzuhören und -sehen...

Franziska Ritter: Mr Mertens, what was priceless for you today?

Gerald Mertens: I made a new podcast recording today with Annette Josef from Mitteldeutscher Rundfunk, who is head of the MDR Klassik department there. And it was such a great conversation, it was priceless.

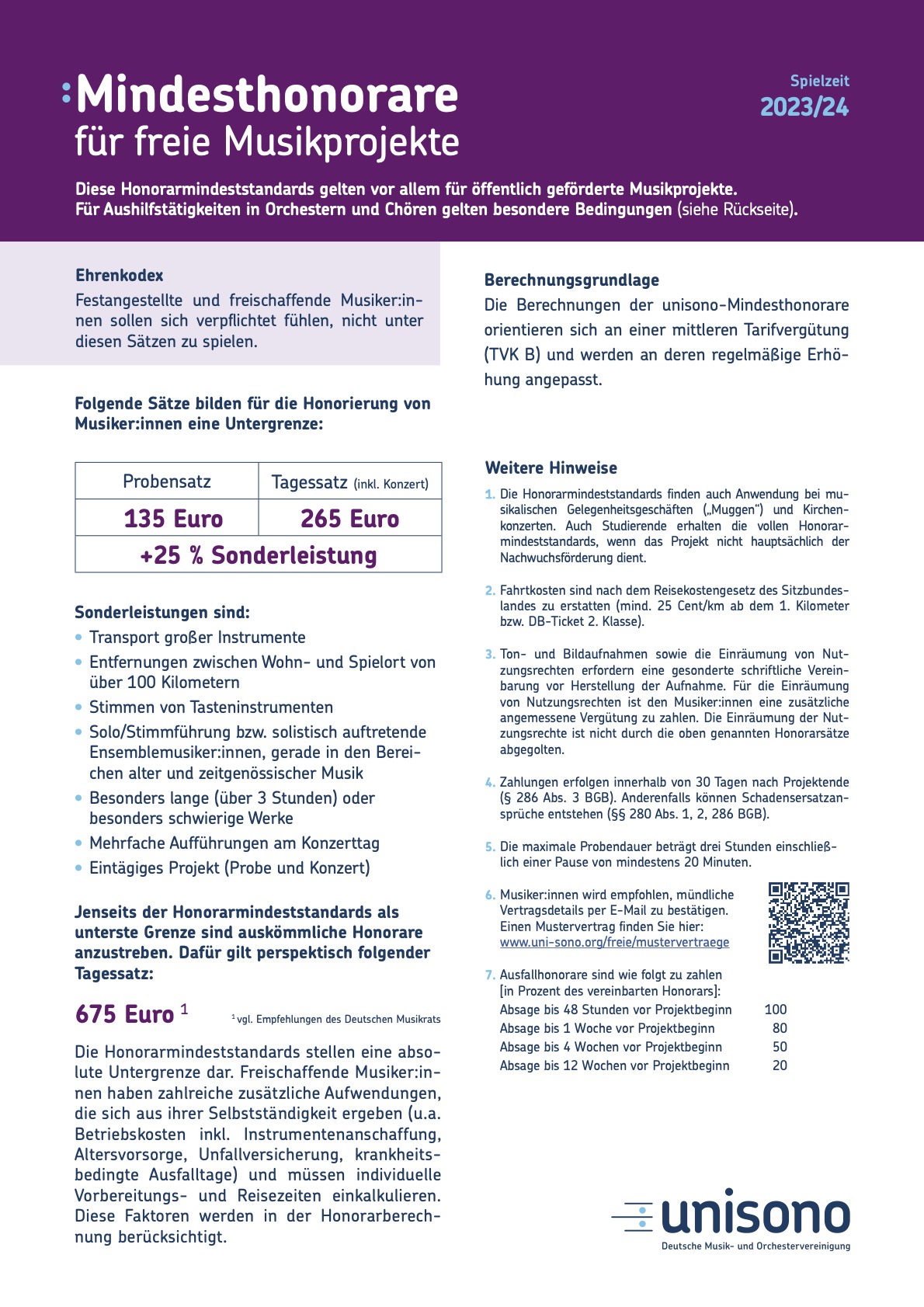

Let's talk directly about affordability: In January 2024, unisono published minimum fees for freelance musicians on its website. And as far as I understood correctly, Mr Mertens, these are actually minimum standards, i.e. absolute lower limits. The recommended daily rate there is €265. Other organisations are also campaigning very strongly for minimum standards, FREO for example for independent ensembles and orchestras. The German Music Council recommends a daily fee of €675 as adequate. Can you give us a brief insight into the negotiation process? And why it is so difficult to enforce these standards in practice in the end?

© Maren Strehlau

© Maren Strehlau

Firstly, you have to involve those affected, i.e. the freelance musicians. We have increasingly done this in recent years, i.e. we always speak from practice for practice. These minimum fee standards were then developed in cooperation with the freelancers and have since been established, because we didn't just pluck them out of the air, but looked at what a comparable orchestral musician earns and transferred them from this collective agreement remuneration, so to speak. By analogy, what does a freelance musician have to earn if they want to achieve a similar income? We took as a basis the average pay scale, i.e. as in a publicly financed orchestra of a municipal theatre. We then derived from this how often a freelance musician has to work in a month, with performances and rehearsals in projects that are financed by the public sector. And what do they actually have to earn to make ends meet? From this, we then developed these minimum fee standards.

In Germany, we have the federal government and the federal states, as well as the municipalities, which are largely responsible for cultural funding. As a rule, the point of contact is the federal government for its own federal projects (the Minister of State for Culture) and the cultural senators and ministers of culture for the 16 federal states. We have approached them several times and have come a long way: The state of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, for example, has now declared the associations' minimum fee standards to be binding and applicable in a corresponding directive. So Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania is comparatively far ahead!

And the Minister of State for Culture has also announced that from 1 July 2024, all federally funded projects will be obliged to comply with the minimum fee standards of the associations and other organisations, e.g. the Early Music Association, Jazz Union or unisono. There are still a few small blurs, because the jazz and rock/pop sector works differently to the classical sector, early music is different to contemporary music and has different funding structures. In any case, at the moment we feel we are further along the road than we have ever been. There's no going back! Corona has also promoted this a little, so that every cultural politician has really realised that we have to do something! The Conference of Culture Ministers - that's the association of the 16 culture ministers and culture senators - has also passed an explicit resolution to establish these minimum fee standards via a fee matrix. We need to convince the other 15 federal states - that's a long road. But we are also working with these federal states and are holding talks with individual heads of department, state secretaries and even ministers to drive this forward.

That sounds like a really important milestone, especially from the summer, when it becomes mandatory for state-funded projects. Let's take a very specific look at the 1:1 CONCERTS format, which is now performed almost exclusively by freelance musicians. As organisers, we are committed to "fair payment". The concerts only last a quarter of an hour each and are for a single person in the audience, making it the least profitable format imaginable from an economic point of view. How would you calculate the fee for a freelance musician here?

It's such a special project that you can't compare it with the others. And 1:1 CONCERTS basically does it in such a way that you give what it was really worth to you and that can be so different. I think that's a good approach, because this "being personally touched by music" and saying: "wow, that really did something for me" or maybe it didn't, but then that's just the way it is. But I think it's exactly this connection between the performer and the listener that gets this point across. If someone is touched by this music and he or she is changed by it, or comes out of the concert differently, ideally transformed, and says "that was such a profound experience for me that I'm prepared to pay €50 for those 15 minutes or maybe just €25, for example". Yes, I wouldn't put a value on that because it's a highly individualised agreement.

Franziska: I'm glad you said that, because the volume of donations in our listeners' donation cycle is actually between zero and €300, often between €25 and €50, and if someone only gives €2, that's perfectly fine. During the pandemic, when the project grew very quickly internationally, we also realised that the much stronger currency is not money, but emotions and resonance, i.e. the tears that flow. The fact that someone listens to me and that someone even writes me a love letter afterwards: that's something incredibly valuable and it stays with me. You can't pay your rent from it, but it's also incredibly important in terms of appreciation for the musicians, who in this world crisis, when people and culture were banished behind the screens, often had to doubt their meaningful musical activity and experienced self-efficacy again in this project.

© Astis Krause

© Astis Krause

The aim of our project was and is to support the freelance musicians, with the help of the orchestra musicians who donated to the project and with the audience donations, scholarships were paid out to the freelancers together with the German Orchestra Foundation as a donation partner. Now, after the pandemic, we play almost exclusively directly with freelancers and therefore we are primarily concerned with one thing: how can we manage to pay our freelance musicians and everyone involved fairly? And what actually constitutes fair payment? I think it's incredibly important that we talk openly about money. Our standard rate for musicians is €200 per hour / 4x 1:1 (i.e. €50 per 1:1 CONCERT / per listener). So we're not that far off, probably even a little above the minimum fee because we don't have a lot of rehearsals beforehand. But that's not enough to organise the concert and the whole thing around it. It's always an exciting negotiation process for us with the regional project teams and funding partners to work out how we can calculate fairly for everyone involved. In this respect, we are delighted when these issues are driven forward at a political level by unisono and the other stakeholders.

But the other thing is appreciation. Let's change our perspective again to the orchestral landscape, to the permanent orchestras, which is a very special workplace, especially in an opera house, where working conditions in an orchestra pit are not at all easy and the highly competitive profession of musician is also characterised by a demanding, long training path. It's not just since the pandemic that we have become so sensitised to topics such as health and mindfulness, new leadership styles and working on an equal footing, as well as other types of collaboration. What is the situation for German orchestral musicians?

Yes, there is no such thing as the archetypal German orchestral musician; instead, there are almost 10,000 people in permanent positions in radio orchestras, opera, concert or chamber orchestras. And there is a very wide range - there are orchestras that are very well organised, where there is an appreciative working environment and the entire orchestra is basically being rethought, e.g. the Staatsphilharmonie Ludwigshafen. There are also other orchestras where things are not going well at the moment, where there is a really, really difficult working atmosphere and where people are frustrated, such as the state orchestra in Kassel or in Wiesbaden.

We are of course in favour of a different management structure, a different management culture in orchestras and that the musician is not only obliged to fulfil what is written in the TVK / in his or her employment contract, i.e.: "You are now Tutti second violin from the moment you join the orchestra until you retire!". Instead, we value him or her as a musician who has other qualifications. However, these are not usually asked for, as chamber music plays an important role, as do moderation activities - there is so much hidden potential in the musicians that many freelancers say: being constrained in this way is not for me - that's why I'm going into the independent scene. And it's kind of abstruse that orchestra members are constrained in such a way that they are frustrated and then live out their artistic activity in chamber music outside of the service or as a soloist or in other ensembles. That's completely crazy. I think we really need to get away from that, because in the private sector, people don't just look at whether this person is only doing this job, but what else this person can do.

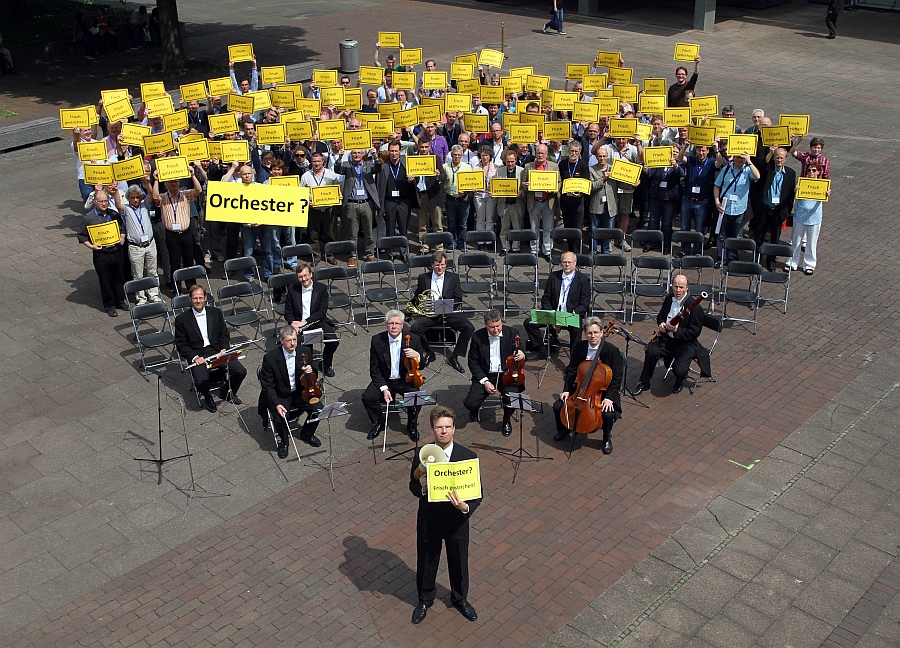

Republikweit - hier in Kiel - unterstützen 2023 unisono-Mitglieder ihre Kolleg:innen von ver.di bei den Streiks im Vorfeld der dritten Runde bei den Tarifverhandlungen.

And if we think in terms of diversity: What enrichment does this person bring to my organisation? That's not asked in the orchestra!

We recently looked it up: our 12,800 unisono association members come from 77 different nations. That's such a wealth that we're asking ourselves how we can take it up and utilise it differently. How can this diversity be incorporated into everyday orchestral life as an enrichment? I see a great deal of potential in the area of job satisfaction and the further development of orchestral organisations by asking even more questions about the musicians' personalities and not just labelling them second fiddle.

And are there any concrete approaches to this? From unisono, for example? What can you do as an association?

On the one hand, we can address and discuss this, which we also do at events, for example at the German Orchestra Day or at the international orchestra conferences, one of which has just taken place in Wroclaw and the next one will be held in Malmö. So we exchange ideas internationally and, of course, also try to cautiously shed light on this "orchestra" model through discussion with colleagues and also with the employer side, which is even more tense and difficult to change in the opera business. But in the concert business, chamber orchestras and concert orchestras in particular have greater opportunities. Radio orchestras are particularly in the spotlight at the moment and still need to develop further. We actually have a lot of potential and we are also trying to empower our own volunteers, orchestra board members and delegates so that they are able to lead this discussion in the organisations.

Let's turn our attention once again to the audience, whose applause is also a kind of currency. And in the direction of ticket prices, where we can of course control a lot and create access or prevent access. Are you also working in this direction as an association?

The topic of audiences has touched us for years, which is why I became chairman of the "Netzwerk Junge Ohren", because today's young audience is tomorrow's adult audience, and we don't just look at the "young" audience, but at various audience groups. We also have to look at older audiences or impaired audiences who can no longer come to the concert hall; we actually cover the whole spectrum.

As far as ticket prices and accessibility are concerned, it has to be said that most of our theatres and orchestras are publicly funded, precisely to ensure accessibility. So if I'm a pensioner and have little money or if I'm a student or pupil, there are very heavily discounted ticket prices so that I can see an excellent performance at an opera or concert for €9 with a big reduction. Fortunately, this is very heavily discounted in Germany. Look at England, look at the USA - the ticket prices there are so astronomically high that this also leads to social exclusion. That doesn't happen in Germany. So from a purely social point of view, it is possible to get into a theatre or an orchestra for just a penny, and I think that's a good thing.

© Florian Arp

© Florian Arp

It's extremely noticeable these days that there are once again unbelievable amounts of strikes and demonstrations. You yourself arrived just in time for our appointment, despite the BVG strike. Postbank is on strike, Lufthansa is on strike, the orchestras in Lüneburg and elsewhere are also on strike. They've had fantastic media coverage and achieved a lot. This lobby is lacking for freelancers and, above all, for solo artists as "lone fighters". What could they do to be heard more?

I can only recommend all those who are travelling as lone fighters to join the relevant associations. After all, associations have the opportunity to really put this "horsepower" on the road. For example, we had the 999 campaign on 9 September 2022, where we stood in front of 16 ministries of education at 9am, freelancers and permanent employees, and presented these minimum fee standards and the corresponding demands to the ministers.

You really have to join forces, you have to organise yourself and not just complain that everything is so difficult and that the arts have no lobby. The arts do have a lobby, but you have to contribute something yourself. Collective labour agreements don't grow on trees either, they only exist because musicians have joined forces to defend their interests. And this is no different for permanent employees in the area of collective agreements than it is for freelancers, who of course face completely different challenges. But precisely because this is the case, we have to join forces and articulate our common interests. And we are trying to organise this to a greater extent.

Thank you very much, Mr Mertens, that's a fantastic closing and I would like to send you off into a priceless evening. Thank you for the valuable conversation.

With pleasure. That was fun.